Music, much like life, is fundamentally a swinging pendulum between tension and release. Fortunately, with music, this is easy to represent objectively and to utilize in your music composition.

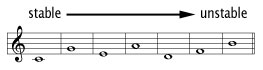

Taking a look at the C major scale, you can see that each note has a relative degree of stability or instability. We also call this consonance and dissonance. Traditionally, the rules of counterpoint dictate that the unison, third, fifth, sixth, and octave are consonances. The unison, fifth, and octave are perfect consonances while the sixth and third are imperfect consonances. The second, fourth, diminished fifth, tritone, and seventh are called dissonances.

It’s important to note that dissonance doesn’t mean being wrong or bad. Dissonance simply indicates an increase in musical tension.

So a diagram of the C major scale, showing the relative degree of stability to instability, would look like this:

How can you use this as a composer?

Think of where you want to take the listener. A melody is like a roller coaster. It goes up, it goes down. It builds tension and releases tension. The final release doesn’t come until the ride is over and you are still again. Your job as a melody writer is to take your listener on a journey, weaving through tension and release just like that roller coaster ride.

A very practical way to illustrate this is to look at the end of melodic phrases. Perhaps your entire melody has 8 melodic phrases. It would make sense to increase tension in the first few phrases by ending on relatively unstable tones. Then you can resolve it, but not completely, on the fourth phrase. Increase the tension again, and then release it completely on the last phrase by ending on the first or fifth scale degree.

This is also a great strategy for improvisation. If you’ve got 32 bars to solo, don’t resolve until the very end. Or, depending on the section that follows, you may want to increase the tension during the entire solo so that the following section can provide the release.

We just looked at how to use tension and release on an entire melody by choosing stable and unstable tones for the endings of melodic phrases. You can also look at the individual melodic phrases and determine the motion between tension and release you would like the listener to feel within each phrase. You can zoom in and out as far as you need to help you create the desired effect.

Obviously, tension and release are created by a combination of factors, like rhythm, harmony, motion, and so on. I’ve only discussed one aspect of tension and release in melody so far. Here’s the bottom line, whenever you need to make a melodic choice, ask yourself, “What level of stability or instability am I trying to create?” Then make the appropriate choice.

L J Schenck says

I enoyed your approach to tension and relaxation in melodic writing. It reminded me of an approach that I studied in a Jazz Theory course that focused on modal approaches to harmony and melody. One of he aspects of the course was with the harmony using the notes that most defined the particular character of the mode that was being used. For example, the F Lydian mode would have the F in the base and the harmonic notes would be something like the #4 (Bnat) of course and then the E to show that it was major tonic/SubDominand and the A to show it was major and maybe the D to distinguish it further. Basically the most definitive notes of the scale was use, but in practice any notes of the mode could be voiced as a chord.

Now for the similiarity. Instead of using ii-V7-I for progressions, there needed to be a nother way of classifying the harmonic progression. We used the Ron Miller text and he rated all the modes and altered modes into a relative dark to light catagory. This is much like the tension and relaxation that you use in your article. Thus you may start with the dark modes and then progress to lighter modes and then back and forth until you came to a resting place.

Both his and your approach reminded me of some of the approaches of Paul Hindemuth’s writings about harmonic progression as well as the rules of the early theorists. I am just so happy to see that others are still listening to music and studying it in these different ways and that there is still good solid music theory thought going on in the music world. Thank you for your article.

If I have condensed my explination too much and you don’t have any idea what I am talking about, please e-mail me

Thanks,

L J Schenck

Graham English says

Thanks for your comment. It makes total sense. Light and dark can be another way to describe tension and release. I’m sure we could come up with many different metaphors to describe all the different continuums that exist in music, as well as in nature.

By the way, I love the sound of Lydian, and especially F lydian. I also like E phrygian which I voice similarly to F lydian. In the right hand from botton to top: F,A,B,E. In the left hand, for F lydian you obviously use an F. But drop it down a half step to E; used in John Coltrane’s “After The Rain.”

David Sprunger says

Hello Graham – great article! I also have posted a video piano lessons titled ‘Tension and Release’ at http://www.playpianotoday.com/tr1

Best wishes!

Joe Russ says

Graham,

What a great and insightful article! I think the tension/release thing is something I’ve done in my writing and guitar playing for years by instinct but it was gerat to read your thoughts on it. I’ve never seen this subject in an article before. I’d love to hear some of your material. I’ve been playing/singing and writing for many, many years and still love it. Recently I was invited to become a featured writer on a new website called Songwriters Marketplace.

(www.songwritersmarketplace.com) I have a number of songwriting articles on there and they have offered to let me do a column on the site. Again, great article and best of luck to you. My email is joeruss56@gmail.com if you would like to stay in touch.

Joe Russ